What econ research says about the effect of immigration restrictions on science

We’ve already heard stories of how the immigration executive order is affecting scientists and harming the scientific enterprise in the process. One thing that the EO is likely to do (or perhaps already has done) is limit the flow of researchers between the US and other countries. A good amount of work has been done in economics that can give us some idea of what effect this will have on science.

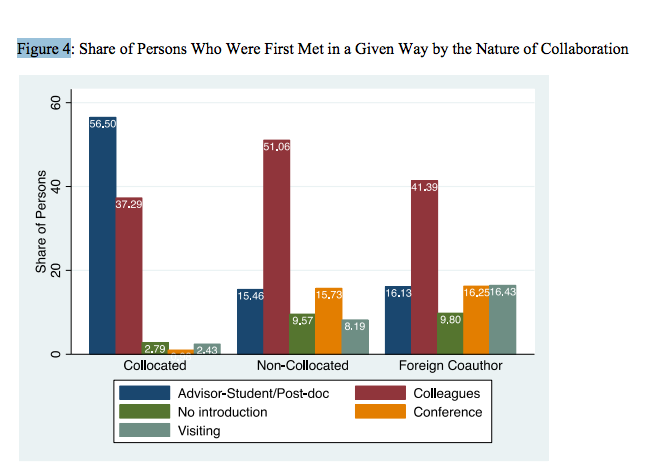

It’s first worth pointing out that scientific collaboration across borders has become more common over the last two decades or so. Freeman, Ganguli, and Marciano-Goroff document that the share of papers coauthored by US and international scientists increased by 23 percentage points between 1990 and 2010. They also conduct a survey of scientists and ask authors how they first met their collaborators.

Look to the right-hand side of the figure from their paper. First meetings as colleagues are the most common, followed by conferences, visiting appointments, and advisor-student/post-doc interactions. These suggest that face-to-face interactions are an important part of establishing collaborative relationships, but you can’t have face-to-face interactions if you can’t travel to a country.

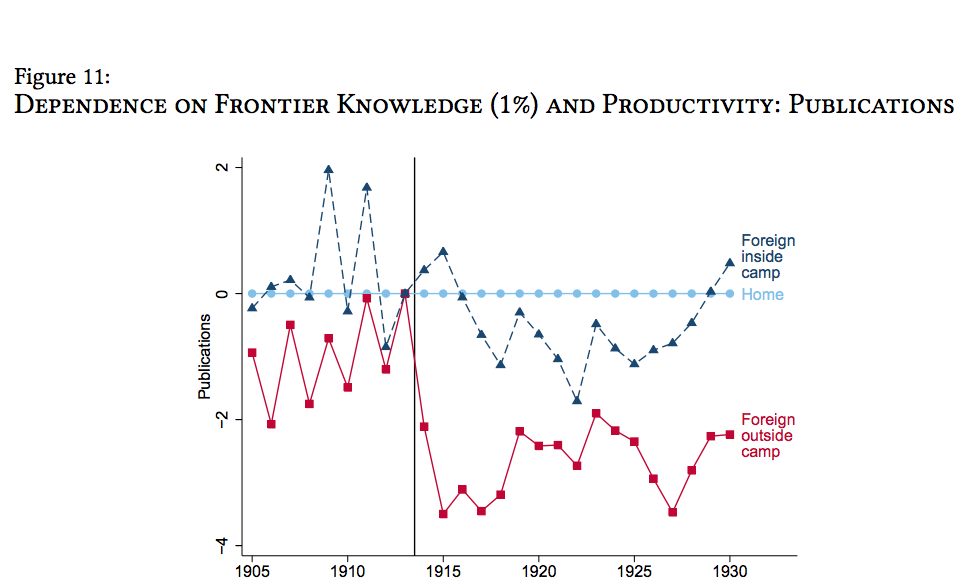

For a historical perspective, Alessandro Iaria and Fabian Waldinger find that the boycott of Central scientists during WW1 lead to a reduction in knowledge flows, which in turn affected the production of what they call “frontier knowledge” or groundbreaking work. During the boycott, access to scientific journals between Central and Allied countries was restricted and conferences were either cancelled or restricted to non-Central scientists. Iaria and Waldinger compare the productivity of US scientists in fields that relied more heavily on knowledge from abroad (e.g. biochemistry, in which Germany was a leader), to US scientists in fields that relied more on knowledge from the US (e.g. biology). The figure below from their paper sums it up pretty well.

Scientists in fields that relied on frontier knowledge from non-US allies (Foreign Outside Camp) experienced a sharp decline in productivity from which they never recovered, while fields that relied on frontier knowledge from US allies (Foreign Inside Camp) experienced some decline but eventually recovered. They also have additional results suggesting that groundbreaking research, measured by Nobel nominations, decreased as well.

The immigration shock we’re experiencing today isn’t perfectly comparable to that in WW1. We aren’t in a war, and communication technologies today may mitigate some of the effects of limiting scientist mobility. But there’s a tremendous amount of uncertainty about what the EO will ultimately cover. Students and colleagues are going to be spooked (rightfully so) and will be much more hesitant about working or attending conferences in the US. There’s pretty convincing evidence, including but not limited to these two papers, that points to the importance of face-to-face interactions in scientific production. We know this intuitively and we have the evidence to back it up: if this immigration mess continues, it will hurt the scientific enterprise.

Leave a Comment